Four Things To Read

One Book

Days When I Hide My Corpse In A Cardboard Box, by Lok Fung, translated by Eleanor Goodman: Lok Fung is the pseudonym of Natalia S. H. Chan, a poet from Hong Kong. Eleanor Goodman, who read for First Tuesdays back in 2022, is a Research Associate at the Harvard University Fairbank Center with numerous translations of contemporary Chinese literature to her credit. As I read this book, navigating the syntactic moves and disjunctions that the almost complete lack of punctuation make visible, I kept thinking about how Goodman focused in her introduction on Fong’s “artistic obsession” with dance. While Goodman’s focus is on dance in the content of Fong’s work, however, I found myself thinking about the way the lack of punctuation in the poems turns the movement of the language into a kind of dance. What I mean is this: the lack of punctuation forces the reader to figure out the syntactical relationship between the clauses and phrases in a poem, in particular where the sentence boundaries are, in the same way that, because there is no obvious “punctuation” in a dance, the audience needs to discern for themselves the interior structure of the movements being performed before them, not just the boundaries–where one section ends and another begins–but also the syntax, because there is a way in which dance, like poetry, cannot help but be linear, that connects and creates relationships between and among movements across those boundaries. I also want to tell you about one other moment in my experience of reading this book. The final poem, “Tale of a Modern Day Knight,” ends with these lines: perhaps it’s a circle, a pattern, a letter/even a riddle, a line of poetry/but I know it absolutely isn’t/a vow.“ I almost never have the experience of finishing a book of poems and feeling the final poem ”click“ into place like a final puzzle piece, but I felt these lines like that. Many of the poems in this book, perhaps all of them, seemed to me to be about proposing what things ”might be“ in order to illuminate by implication what the speaker knows for sure, and wants the reader to know for sure, that they are not. Here, for example, are two lines from ”October in the City: A Book of Amnesia:“ When the sick city lies down and becomes an occupied stone/the canals of the body stir the consciousness awake. This is my entirely intuitive response, but, for me, the subtext of these lines, and of much of the book as a whole, mirrors the structure of the lines from ”Tale of a Modern Day Knight:" perhaps this is what the city is and perhaps this is what living in that city feels like, but knowing this means we know for sure that the city and its inhabitants are not [and then you need to fill in the blank here with your understanding. Each of the poems in this book seems to me to be a journey through some variation of that proposition. It’s a journey worth taking.

Three Articles

In a Poem, Just Who Is ‘the Speaker,’ Anyway?, by Elisa Gabbert: “The question here, the one I think my friend was asking, is this: Does our use of “the speaker” as shorthand — for responsible readership, respectful acknowledgment of distance between poet and text — sort of let us off the hook? Does it give us an excuse to think less deeply than we might about degrees of persona and spokenness in any given poem?” I like this question a lot, and I like the way Gabbert teases out the implications of using the term “speaker,” as opposed to persona, as a way of acknowledging the distance between the person writing a poem and the voice that person constructs to speak in and through a poem. It’s not quite, as she suggests a persona, the way the speaker in a dramatic monologue, a la Robert Browning, is a persona, but it is, or at least can be, as she says elsewhere, a way that “the poem always gives my own I, my mind’s I, the magic ability to say things I wouldn’t in speech or in prose.” In my own work/practice, I don’t experience this as magic, though I understand why someone else might. Rather, for me, the poem is a field, or a context, or a staging area, or a path where I can say the things I need to say, whether they are autobiographically true or not, to map the emotional territory the poem explores. I was at a conference recently where a poet, speaking about the way her work reflected her autobiography, said explicitly, “I am the speaker of my poems,” claiming the gap between poet and speaker-of-the-poem as part of who she is. I’m not sure she was saying that everything in her poems is factually, autobiographically, true, but if that was what she meant, then I think she was being disingenuous about herself and her art. If, on the other hand, she meant that the speaker of her poems is no less a part of her than her factual, autobiographical self, and that it can therefore be meaningfully talked about as her, then I think she said something very much worth thinking more deeply about.

The Poet Who Commands a Rebel Army, by Hannah Beech: “The commander, Ko Maung Saungkha, has raised an army of 1,000 soldiers. But his background is not military. Instead, he is a poet, one of at least three who are leading rebel forces in Myanmar and inspiring young people to fight on the front lines of the brutal civil war.”W. H. Auden wrote in “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” that “poetry makes nothing happen,” which has always sounded to me very much like the Daoist exhortation to “do nothing,” which, as I understand it, is not a call to inaction, but rather a call against trying to force something specific to happen; and Auden seems to see poetry in a similar vein, because he goes on to say that poetry “survives” as, or because it is, “a way of happening.” It’s interesting to think about that in the context of what Beech reports on in this article about a Myanmar poet, Ko Maung Saungkha, who has become a military leader in the war against that country’s dictatorship. “Myanmar,” Beech writes, “is a country entranced by poetry. Poets are celebrities, accorded the kind of adulation that, in other places, might be showered on actors or athletes. And verse, delivered in punchy rhymes made easy by the Burmese language, has long been political, used to galvanize the masses.” Myanmar, in other words, seems to be a country where poetry can indeed make something happen, and the government seems to know that. “Since the coup,” Beech goes one, “at least half a dozen poets have been killed, as the military junta crushes dissent. More than 30 poets were imprisoned in the aftermath of the coup, according to the National Poets’ Union.”

A 12-Minute Show, Played Only Once, Just Might Live Forever, by Chris Almeida: “This is modern drum corps. It is a competition for mostly college-age students, but the groups are not affiliated with any schools. When they are in season, the corps consume the lives of their members — perfecting a single performance, and then continuing to drill it until it is somewhere beyond perfection. Rehearsals last up to 12 hours a day, and intense tours dominate the performers’ lives in July before culminating in a world championship in Indianapolis…The activity is a study in passion — or perhaps delusion. It is not easy. It does not make money. It does not clearly translate to a career. And it ends; groups like the Bluecoats that compete in Drum Corps International’s world-class division are made up exclusively of participants under the age of 22.” I wrote a little bit in Four by Four #19 about playing bass baritone bugle in my neighborhood drum corps when I was a teenager. I don’t think, though, that I have ever seen drum corps get the kind of coverage that it gets in this article, which comes pretty close to describing what drum corps do as pursuing art for art’s sake. The point made by the title is worth unpacking a little bit, since it is true that each drum corps performance is a once-in-a-lifetime thing, except for the encore performance that the world champion corps gets to play. Putting that performance together is a nearly non-transactional experience for the young people who participate, which I thought about a lot while reading the article, given how transactional life in general has become, especially in the college classrooms where I teach.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

All these images, taken from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are in the public domain.

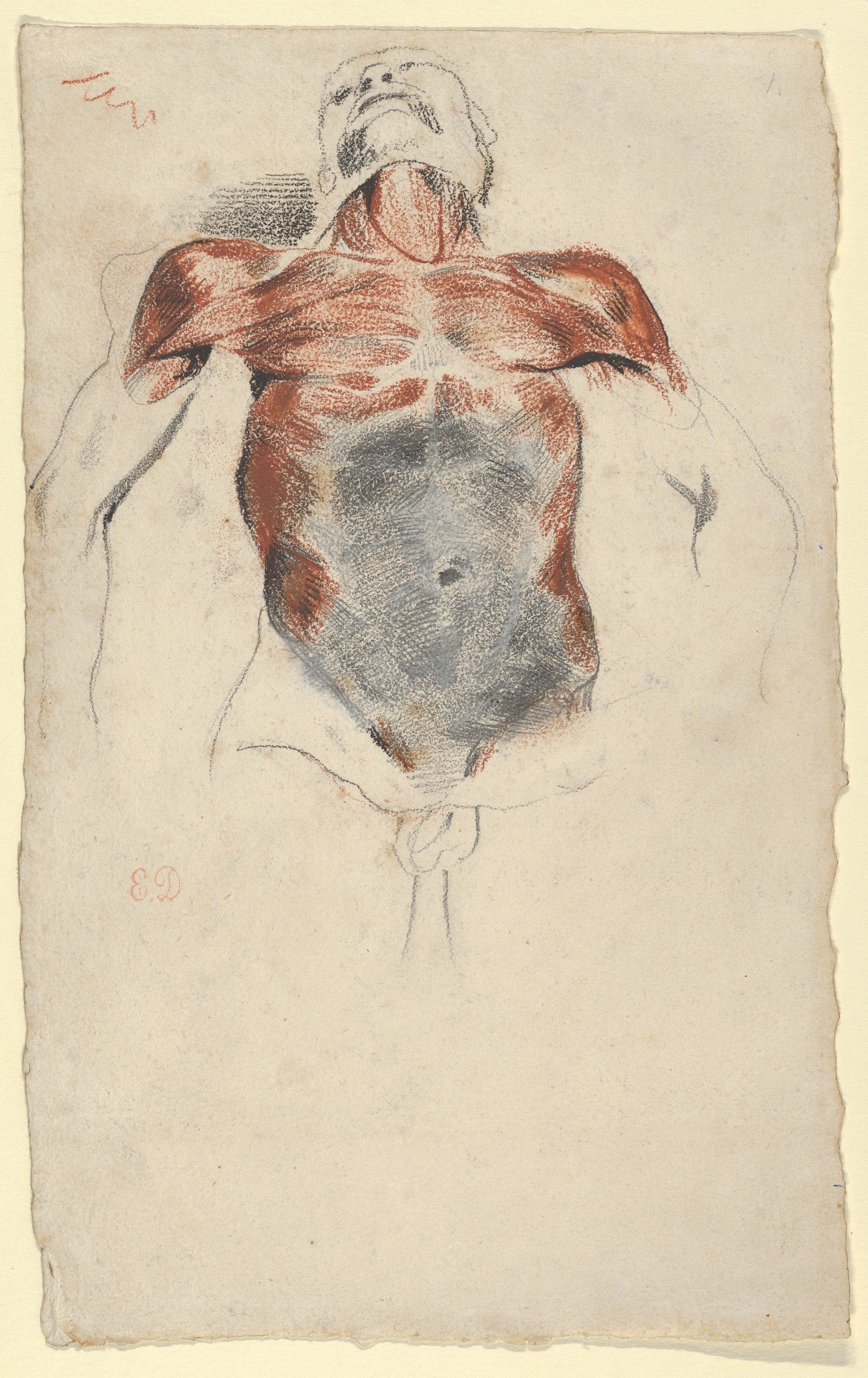

Ecorché- Torso of a Male Cadaver

Eugène Delacroix, French, 1828?

The posthumous sale of the contents of Delacroix’s studio contained 126 of his anatomical drawings. None of the known surviving examples are dated, and Delacroix never mentioned the practice in written accounts. However, a drawing by the sculptor Henri de Triqueti of a corpse in a pose similar to this one records Delacroix’s presence with him at a hospital in June 1828. This work may derive from that same visit. Triqueti’s testimony makes clear that this was not an activity restricted to Delacroix’s student years. By this time, Delacroix had exhibited paintings in three Salons and earned considerable renown.

Portable diptych sundial

Probably by Charles Bloud, ca. 1666–80

Although Charles Bloud (1653-1699) was the inventor of this variety of azimuth sundial, several other Dieppe sundial makers, including Gabriel Bloud and Jacques Senecal, are known to have made and signed similar sundials. The principle by which their sundials worked is based on a variation in the magnetic declination of the area around Dieppe which existed for only a short period in the seventeenth century, beginning about 1666.

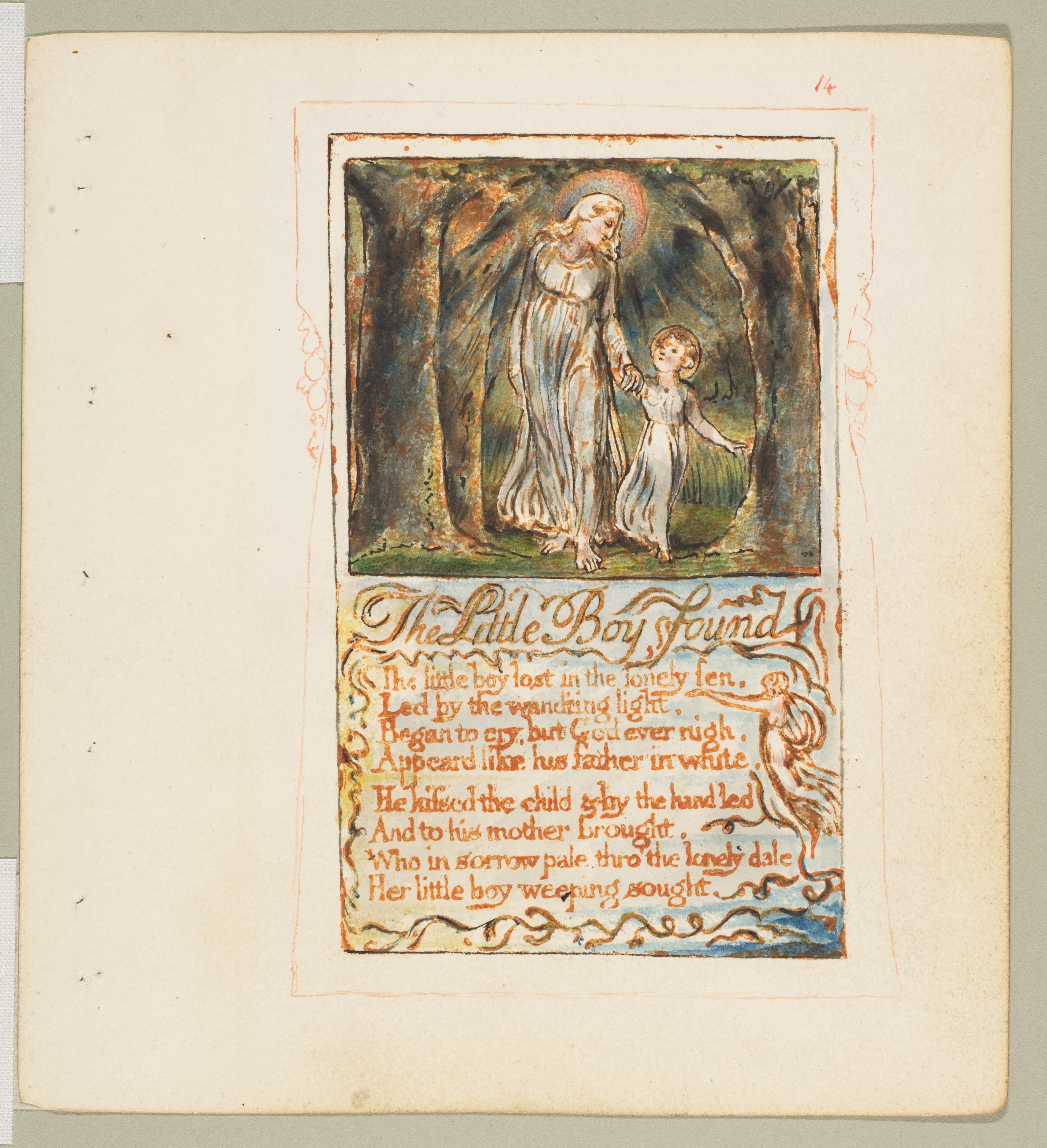

Songs of Innocence- The Little Boy Found

William Blake, 1789, printed ca. 1825

Blake etched twenty-seven printing plates for Songs of Innocence in 1789, completing those for the Songs of Experience in 1794. He then printed and hand-colored copies of the combined sets over succeeding decades as patrons ordered them, each one visually distinct. Verse and image work together to celebrate poetic inspiration and reveal aspects of the divine as expressed through nature. The poetic voice is often that of a child, whose emotions range from delight to fear, with darker feelings usually resolved in the earlier Songs of Innocence by adult intervention. This first group of Songs was shaped by the heady early days of the French Revolution, when British liberals and radicals believed that true reform was imminent on both sides of the Channel.

The artist Edward Calvert met Blake around 1825 and commissioned this copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience soon thereafter. These richly decorated pages, with their deeply saturated hues and distinctive ornamental borders, reveal Blake’s late vision and the order is established by small red numbers at upper right.

Study of the left hand and arm of Meditation

Auguste Rodin, modeled ca. 1894, cast before 1912

Four Things To Listen To

Each of these pieces is from The Blue Notebooks, by Max Richter. Richter originally composed the piece in the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and described it "a protest album about Iraq, a meditation on violence – both the violence that I had personally experienced around me as a child and the violence of war, at the utter futility of so much armed conflict." Perhaps these four selections will inspire you to listen to the entire album.

The Blue Notebooks

Shadow Journal

On The Nature of Daylight

Horizon Variations

Four Things About Me

I am afraid of roller coasters, of any amusement park ride designed to leave your stomach in your mouth or make you dizzy or both at the same time. I have no idea why, but I remember very clearly being at Coney Island with my father and my brother when he and were little boys. We were on some kind of tilting and spinning ride and I was crying. I have this memory of my father reaching over and trying to comfort me, reassuring me that it would be over soon, though of course it wasn’t over sooner enough; and I remember clearly feeling betrayed. He had talked me into trying the ride by saying that it wouldn’t go very fast, that it spun very slowly, and that he’d be right next to me the whole time. It went way too fast; the spinning made me nauseous; and while it was true that he sat next to me, that fact did absolutely nothing to calm the fear and near panic that set in almost as soon as the ride started.

I get my love of reading from my mother. I only remember the titles of two books that I pulled from the shelves that were in our living room—The Other, by Thomas Tryon, which gave me nightmares, and The World Is Made Of Glass, by Morris West, which I also wrote about in Four by Four #21—but I knew reading was important to her and that sense of importance is what I absorbed as much as anything else. (I know I read more than those two books—she had, for example, some volumes of Victorian pornography that I know I read—but I don’t remember the titles.)

When I was a graduate student in Syracuse University’s Creative Writing MA program in the mid-1980s, my friends and I used to go dancing at a place called, appropriately enough, POETS, which stood for Put Off Everything Till Saturday. I still think that’s a cool name for a bar with a dance floor in a college town. My wife, though, receives a mail order catalogue for women’s clothing–the old fashioned kind, in the mail–and its title is Poetry, which is bad enough, but, as far as I can tell, there is nothing in the interior of the catalogue that capitalizes on the title in any way, shape, or form. Here’s an example of what the cover looks like:

When I was in seventh grade—my teacher’s name was Mr. Kaiser—I won second place in my junior high school’s science fair. Using, if i remember correctly, a piece of meat, I grew a culture in a petrie dish, documenting how long it took for me to be able to see microorganisms through the microscope we had in our classroom. Then I froze the culture and documented how long it took after I thawed it out for microorganisms to reappear. I must have articulated a hypothesis I was trying to prove, though I don’t remember what it was, and so I don’t remember what I thought the experiment showed, but I know that I called it an experiment in cryobiology. Back then, my primary academic interest was science, not English, though it was a toss up as to whether I would pursue biology or—I was also learning to write programs in Basic—computer science. I was very disappointed, therefore, when I switched schools and went to yeshiva. Unlike the junior high school I’d attended the previous year, they had no computers. Their computer science program consisted of teaching us how to program using Fortran punch cards. They also didn’t have microscopes or any of the other equipment we had in the junior high school, and I did not like the woman who was our science teacher. I don’t know if I would have ended up a literature person anyway, but those two factors nudged me in that direction and, by the time I graduated, there was no question that writing and literature were my primary academic interests.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.