Four Things To Read

All The Ways We Lied, by Aida Zilelian: The last sentence of this novel is “Because after all, there was freedom in being loved.” When I read those words, I felt keenly how much I enjoyed and was moved by the winding path along which the novel earns that sentiment. The story revolves around a family that is, in many ways, on the verge of falling apart. The narrative traces the path by which they manage to stay connected to and committed to and loving of each other by individuating, finding out who they are as people not wholly defined by their (sometimes comically rendered) deeply dysfunctional family dynamic. If you’ve ever had to figure out how to love someone who seems hell bent on making it difficult to love them—and especially if you have any experience, vicarious or otherwise, with how that dynamic can play out in an immigrant family—you will both enjoy and identify with the four women, a mother and three sisters, who are the main characters of this book.

§§§

The Room Where I Was Born, by Brian Teare: When CavanKerry Press published my first book, The Silence of Men, in 2006, I thought it was also the first book of poems explicitly to take on the experience of being a male survivor of childhood sexual violence. I was wrong. Brian Teare’s The Room Where I was Born, which I just finished and which won the 2003 Brittingham Prize in Poetry, preceded mine by, obviously, three years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we dealt with the subject matter in very different ways. Teare is concerned in his book with making poems that give form and meaning to the ways in which childhood sexual violence disrupts, corrupts, warps, and otherwise undoes the survivor’s sense of reality. Those poems are about naming that experience as much as they are about naming the experience of violation itself. The Room Where I Was Born also explores Teare’s coming to terms with being gay in the context of the sexual violation he experienced and the homophobia of both the place where he grew up and our culture at large. I am glad to have read this book, which was recommended to me by Rob Arnold, the executive director of Poets House.

§§§

The Spectre of Patriarchy, by Roberto de Mattei:

At this point, Prof Ricolfi poses an obvious question: how can one speak of a patriarchal society when the figure of the father has disappeared not only from the family but from society more generally?

Mattei wrote this piece in response to an editorial in the Italian newspaper I’ll Messaggero, by Professor Luca Ricolfi, a sociologist, who believes that “in Western societies the distinctive traits of patriarchal societies have almost entirely disappeared.” Ricolfi goes on to argue that violence against women is the “result…of the defeat of patriarchy.” It’s an important argument to understand, if only because I predict we are going to hear it more and more frequently here in the States in the months and years to come.

§§§

Facing 8 Years in Prison, a Director Flees Iran, by Amir Ahmadi Arian:

“[The Seed of The] Sacred Fig” offers [a] provocative exploration of…the myriad injustices Iranian women have to endure in their daily lives. “In my early movies, women were far from the center,” Rasoulof says. “At one point I looked back and noticed that I had not created a single round, compelling female character. I knew very little about women’s lives, and I decided to rectify that.”

This article, which tells the story of Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof’s career and his decision to escape from Iran, is also notable for its brief history of Iranian cinema since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. It’s worth reading for both.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

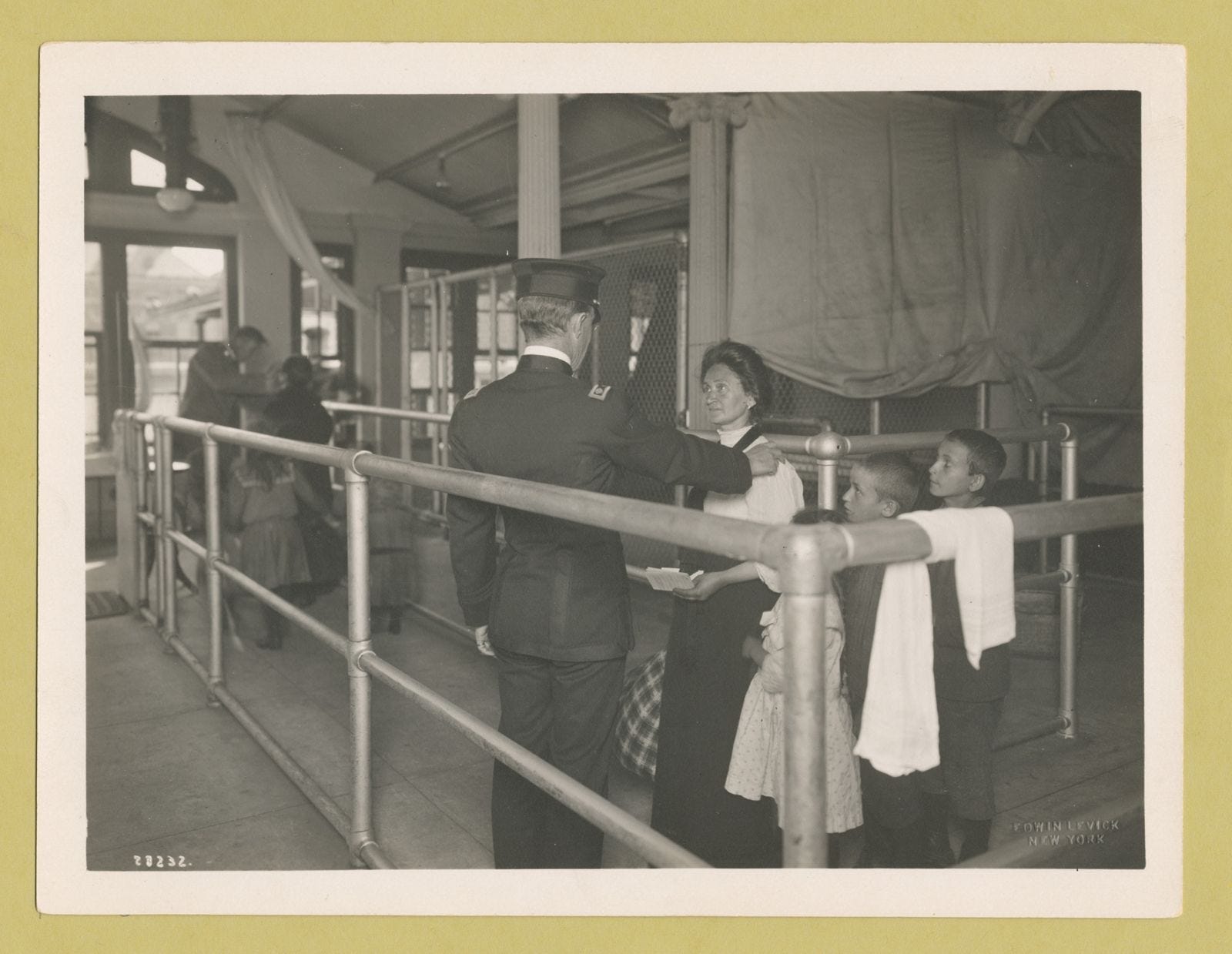

All images are from the New York Public Library’s Collection of Ellis Island Photographs taken between 1902 and 1913 and are in the public domain.

A group of immigrants, most wearing fezzes, surrounding a large vessel which is decorated with the star and crescent symbol of the Moslem religion and the Ottoman Turks

§§§

Group photograph captioned 'Hungarian Gypsies all of whom were deported' in The New York Times, Sunday Feb. 12, 1905

§§§

Immigrants undergoing medical examination

§§§

The pens at Ellis Island, Registry Room (or Great Hall). These people have passed the first mental inspection.

Four Things To Listen To

Charles Valentin Alkan - 25 Préludes, Op.31: No. 8, La chanson de la folle au bord de la mer

§§§

Egberto Gismonti - Maracatu

§§§

Fatoumata Diawara - Sonkolon

§§§

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds - Push the Sky Away

Four Things About Me

The first time I remember hearing the word period used to refer to menstruation I was in fifth. That week, the girls had been show a filmstrips about puberty. (The boys, because we were considered less mature than the girls, would not see it till the following year.) My friends and I were hanging out in the courtyard of the garden apartments where we lived, and one of the girls—I’m pretty sure it was Gina—started teasing us that boys “didn’t know what a period was.” I don’t remember anything about the rest of the conversation, except that Gina did eventually tell me—and I think she may have told only me—that it meant the monthly bleeding that began when a girl reached puberty. In my memory, this was not actually news to me, though I don’t remember why I knew about it. I had never before heard it called a period, though, and that seemed more strange to me than the biological fact itself.

§§§

Another encounter that I had with menstruation, probably around the same time, was at our neighborhood’s public pool. I have a clear memory of a Black girl in a yellow bathing suit walking with her mother away from the side of the deep end where I was swimming, while trying to cover with one hand the bright red stain that it was impossible to miss near her butt. Given how white and racist our neighborhood was, I find it hard to imagine that the girl and her mother were actually from the neighborhood—and, in fact, I am surprised that I have no memory of anyone saying anything to them. In my memory, though I have no idea how reliable this is, the girl is the daughter of my mother’s friend Vivian, who had come for a visit. What I remember most clearly, is feeling tremendous sympathy for how embarrassed the girl must have been as she and her mother walked to where their towels were so the girl could wrap one around her waist; and I remember as well feeling strongly how different my own body was from hers and how incomprehensible her experience seemed to me.

§§§

I fell in love in my twenties with a woman I was in a relationship with for around seven years. We met at the summer camp where we were both counselors and we very quickly became good friends. She was not-quite-yet-engaged to the man she thought she was going to marry; but she was, she explained, also seeing another guy who worked at camp, because she wanted to make sure that the first guy really was the one she wanted to marry. We were both very clear as our friendship developed that we did not want to turn that triangle into a square. Still, the more we talked, the closer we became, and she and I eventually ended up together. That didn’t happen at camp, though. We fell in love after engaging in what would have been a perfectly conventional Victorian courtship. After camp was over—and this went on for a couple of year, if I remember correctly—we wrote long letters in which we revealed ourselves in ways we would not have been able, and likely would have chosen not, to do in person. That kind of letter writing, not just between lovers, but between friends as well, was still common during my lifetime. I miss it. Email just doesn’t cut it.

§§§

I wrote in Four by Four #11 about Rabbi Wehl, the gemara rebbe in whose class I first learned the lesson of “loving the questions.” When it came to the question of how committed his students were to living his version of an authentic Jewish life, however, Reb Wehl could be a real son-of-a-bitch. At least once a week during the fall—or at least it was that frequent in my memory—he would go on a rant about how shameful it was (a shonda!) that our parents would spend twenty or thirty dollars on a turkey for Thanksgiving, but they wouldn’t spare a dime for a set of Mishneh Torah, Maimonides’ attempt to write a comprehensive treatment of all of Jewish law, including those laws that only applied when the temple stood in Jerusalem. At some point that year—this was 10th grade—he found a bookseller willing to sell his students a five volume set for five dollars. He put so much pressure on us that there was no way not buy a set, which I was reluctant to do because my Hebrew was nowhere near good enough for me to be able to read the book on my own. So I convinced my mother to give me the money. Every once in a while I would try to read it and then give up. The books stayed on my shelf for a long time before I got rid of them. While I am sure I did not throw them in the garbage, I have no memory of what actually happened to them.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.